PeB Journal | Analysis, General, International Politics, Opinions, Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

As students of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University, members of the Pax et Bellum Journal team were recently discussing different conflicts that we have examined throughout our previous study – during this discussion it became apparent that while we could list quite a few, there are still numerous current and historic conflict we know fairly little about. As a result, we decided that at the end of every week, one person would present a chosen conflict. While these ‘conflict briefs’ are only meant to give a short overview of current and historical conflicts, we decided to share these ‘briefs’ in weekly blog posts – starting with the non-violent conflict between Taiwan and China.

The articles published do not reflect any stance taken by the organization Pax et Bellum; they only reflect that of the author. If you have any questions or comments please email us (journal@paxetbellum.org).

Context

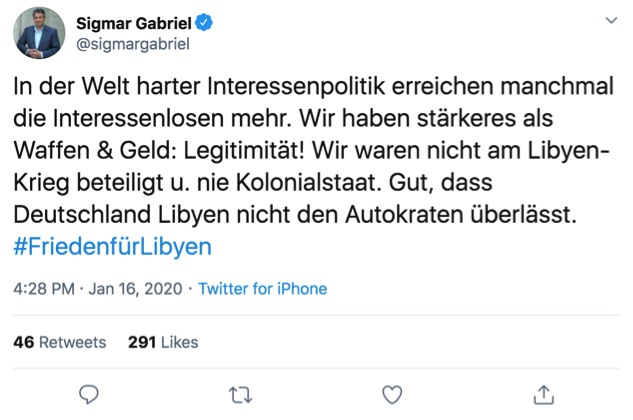

On January 16th 2020, the former leader of the German Social Democrat Party (SPD) tweeted the following:

This roughly translates to:

“In a world of hard-interest politics, the uninterested sometimes achieve more. We have more than weapons & money: legitimacy! We were not involved in the war in Libya and were never a colonial state. It is good that Germany is not leaving Libya to the autocrats. #FreedomForLibya.”

With this statement, Mr. Gabriel has laid bare his fundamental ignorance towards not only German interests and actions abroad – weapons exports totaled almost € 1.8 billion in the year 2019, including to actors involved in the Yemen conflict (UAE) and Libya’s neighbour, Egypt, thus clearly demonstrating the ‘uninterestedness’ Germany currently expresses in the world (Deutsche Welle [DW] 2019) – but also Germany’s history as a colonial actor. But do not worry Mr. Gabriel, ignorance has a cure.

Imperial Germany as a Colonial Actor

While Germany is perhaps not the first country that comes to mind as a former colonial power – the United Kingdom and France have that particular honour (Blackshire-Belay, 1992) – from 1884-1885 onwards Imperial Germany “[…] declared that the German Empire would join the European scramble for colonial possessions” (Wempe, 2019, pp. 1). By 1913, Imperial Germany possessed the third largest colonial empire in the world that included territory in China, island colonies in the Pacific, and large swaths of land on the African continent, such as German East Africa (now Tanzania), Cameroon, Togo and German South-West Africa (now Namibia) (Wempe, 2019, pp. 1). For decades, Imperial Germany, like its European compatriots, utilised and profited from the expression of their ‘hard interests’ abroad in their colonies. However, in 1918, following defeat during World War I and marked by the signing of the Treaty of Versailles “[…] the German Empire—both overseas and in Europe itself—was nothing more than a memory” (Wempe, 2019, pp. 1). A memory which dear Mr. Gabriel has seemingly conveniently misplaced.

Herero and Nama Genocide

On one hand, as stated above, the memory of Imperial Germany was short-lived and vastly overshadowed by more recent atrocities of the 20th century – the Armenian genocide, the Rwandan genocide and the Holocaust to name only a few – however, Mr. Gabriel’s tweet is especially ignorant when considering it in the context of the following: during Imperial Germany’s time as a colonial actor, it committed the 20th century’s first genocide. As per the definition of the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), genocide falls under the catagory of one-sided violence or “the deliberate use of armed force by the government of a state or by a formally organised group against civilians which results in at least 25 deaths in a year” (UCDP, n.d.).

In October 1904, the Imperial German General Lothar von Trotha, gave a Vernichtungsbefehl or extermination order, in response to a rebellion staged by the Herero and Nama people in its South-West Africa colony (de Souza Correa, 2011). While a large number were killed directly, others fled into the Kalahari desert to escape the violence or were forcibly placed in internment camps, as a result, many subsequently died of starvation, dehydration and disease (Steinmetz, 2007; Lehmann, 2014). Between 1904-1908, the Herero population in South West Africa alone was reduced from 80,000 to roughly 15,000 refugees (Whitaker, 1985). The exact number of victims of the Herero and Nama genocide remain unknown, but it is estimated that more than 100,000 members of both groups were killed as a result of Lothar von Trotha’s order (Kuss, 2017).

Despite the extent of one-sided violence committed by the Imperial German colonial power, it took over a full century for the modern state of Germany to acknowledge responsibility and recognise that the extent of violence committed constituted these actions as genocide. Only in 2015 did the speaker of the German Parliament officially acknowledge that the violence perpatrated by Imperial Germany between 1904-1908 by Imperial Germany was in fact a genocide (van Hammerstein, 2016; Kössler & Melber, 2012).

Conclusion

It is because of the viciousness of the violence committed by Germany as a colonial actor and the long road to recognition of this crime, that make Mr. Gabriel’s above statement absolutely unacceptable – let alone for a man who was part of the German government during a time in which attempts were made to mend ties with Namibia (Kössler & Melber, 2019).

In conclusion, this author would like to congratulate Mr. Sigmar Gabriel – Congratulations for joining a long line of German politicians who have denied or down-played atrocities committed in Germany’s name. You’re in good company.

Sources

Source image: https://www.europeana.eu/portal/de/record/9200290/BibliographicResource3000095282 568.html (German colonies marked in red – Togo, Cameroon, German South-West Africa, and German East Africa

Blackshire-Belay, C.A., 1992. German Imperialism in Africa: The Distorted Images of Cameroon, Namibia, Tanzania and Togo. Journal of Black Studies, 23(2), pp. 235–246.

Deutsche Welle, 2019. Germany’s arms export approvals headed for record high. Online. Available from: https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-arms-export-approvals-headed-for-record- high/a-50730209 [Accessed 2 February 2020].

De Souza Correa, S. M., 2011. History, memory, and commemorations: on genocide and colonial past in South West Africa. Revista Brasileira de História, 31(61), pp. 85-103.

Kössler, R. and Melber, H. 2012. Remembrance is the most powerful weapon against genocide. Online. Available from: https://theconversation.com/remembrance-is-the-most-powerful-weapon-against-genocide-5049 [Accessed 2 Febraury 2020].

Kössler, R. and Melber, H. 2019. Has the relationship between Namibia and Germany sunk to a new low? Online. Available from: https://theconversation.com/has-the-relationship-between-namibia-and-germany-sunk-to-a-new-low-121329 [Accessed 2 February 2020].

Kuss, S., 2017. German Colonial Wars and the Context of Military Violence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lehmann, P., 2014. Between Waterberg and Sandveld: An Environmental Perspective on the German–Herero War of 1904. German History, 32(4), pp. 533–559.

Steinmetz, G., 2007. The Devil’s Handwriting: Precoloniality and the German Colonial State in Qingdao, Samoa and Southwest Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

UCDP, n.d. Definitions. Online. Available from: https://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/definitions/ [Accessed 2 February 2020].

von Hammerstein, K., 2016. The Herero: Witnessing Germany’s “Other Genocide”. Contemporary French and Francophone Studies, 20(2), pp. 267-286.

Wempe, S. A., 2019. Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations. New York: Oxford University Press. Whitaker, B.C.G., 1985. Revised and updated report on the question of the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide. Online. Available from: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/108352?ln=en#reco rd-files-collapse-header [Accessed 2 Feb. 2020].